Dr. Elliot McGucken · 22 November 2025 Originally published on Medium · August 25th, 2025 Download Paper 1 The McGucken Invariance: Download Paper 2 The McGucken Invariance:

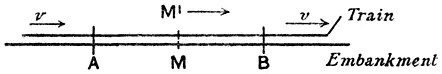

Let us quickly revisit Chapter 9 of Einstein’s wonderful Special and General Relativity where we see the following figure and description:

Fig. 1. Are two events (e.g. the two strokes of lightning A and B) which are simultaneous with reference to the railway embankment also simultaneous relatively to the train? We shall show directly that the answer must be in the negative.

Let us suppose that the train is moving at .99c to the right. Firstoff, we must note what Einstein missed and never discusses. The light that M’ observes emanating from point A will be far dimmer than the light that M’ observes emanating from point B. This is due to several factors, including the fact that when the light from point A reaches M’, M’ will be quite far away, as M’ is moving to the right at .99c, and the intensity of light falls off as the distance squared. On the other hand, when the light emanating from B reaches M’, M’ will be quite close to B, and the light will be far brighter. There is a measurable asymmetry in this thought experiment which Einstein does not address. While M will observe the brightness of the light form A and B to be the same, M’ will observe the light from B to be far brighter than A.

There is another measurable asymmetry in this thought experiment which Einstein does not address. While M will observe the frequency of the light from A and B to be the same, M’ will observe the light from B to be blue-shifted, and M’ will observe the light from A to be red-shifted.

So it is that by observing the frequency and intensity of the light from A and B, M’ would be able to calculate the velocity at which they are moving, and they would be able to contemplate the frame of M in which the flashes from A and B arrive at M at the same time with the same brightness and frequency. So it is that M’ would have knowledge of the simultaneity which M observes, an M’ would be able to agree with that notion of simultaneity.

Furthermore, as all measurement is a quantum in nature, as M’ zooms away on the right, the light from A grows ever-dimmer, and at some point, depending on the brightness of the original lightning flash and the velocity of M’, there is a chance that the light from A will not be observed.

IX The Relativity of Simultaneity

Up to now our considerations have been referred to a particular body of reference, which we have styled a “railway embankment.” We suppose a very long train travelling along the rails with the constant velocity v and in the direction indicated in Fig. 1. People travelling in this train will with a vantage view the train as a rigid reference-body (co-ordinate system); they regard all events in reference to the train. Then every event which takes place along the line also takes place at a particular point of the train. Also the definition of simultaneity can be given relative to the train in exactly the same way as with respect to the embankment. As a natural consequence, however, the following question arises:

Fig. 1. Are two events (e.g. the two strokes of lightning A and B) which are simultaneous with reference to the railway embankment also simultaneous relatively to the train? We shall show directly that the answer must be in the negative.

When we say that the lightning strokes A and B are simultaneous with respect to be embankment, we mean: the rays of light emitted at the places A and B, where the lightning occurs, meet each other at the mid-point M of the length of the embankment. But the events A and B also correspond to positions A and B on the train. Let M′ be the mid-point of the distance on the travelling train. Just when the flashes¹ of lightning occur, this point M′ naturally coincides with the point M but it moves towards the right in the diagram with the velocity v of the train. If an observer sitting in the position M′ in the train did not possess this velocity, then he would remain permanently at M, and the light rays emitted by the flashes of lightning A and B would reach him simultaneously, i.e. they would meet just where he is situated. Now in reality (considered with reference to the railway embankment) he is hastening towards the beam of light coming from B, whilst he is riding on ahead of the beam of light coming from A. Hence the observer will see the beam of light emitted from B earlier than he will see that emitted from A. Observers who take the railway train as their reference-body must therefore come to the conclusion that the lightning flash B took place earlier than the lightning flash A. We thus arrive at the important result:

Events which are simultaneous with reference to the embankment are not simultaneous with respect to the train, and vice versa (relativity of simultaneity). Every reference-body (co-ordinate system) has its own particular time; unless we are told the reference-body to which the statement of time refers, there is no meaning in a statement of the time of an event.

Abstract

In this paper, we introduce the McGucken Invariance, a novel relativistic invariant derived within the framework of special relativity. This invariant combines the time of arrival (tau), observed frequency (f′), and observed brightness (I′) of light signals from stationary sources, as perceived by an observer in a moving inertial frame. Drawing from Einstein’s classic thought experiment on the relativity of simultaneity, we extend the analysis to incorporate the relativistic Doppler effect and the transformation of radiation intensity.

The invariant takes the form:

tau * (f’)^2 / (I’)^(1/4) = L * gamma * f^2 / I^(1/4)

Introduction

Special relativity fundamentally alters our understanding of space, time, and the propagation of light. A pivotal illustration is Einstein’s thought experiment involving lightning strikes on a railway embankment observed from a moving train, which demonstrates the relativity of simultaneity.

Beyond simultaneity, relative motion induces the relativistic Doppler effect, shifting the frequency and wavelength of light, and alters the observed intensity (or brightness) through Lorentz transformations of the electromagnetic field. The intensity transformation arises from the Lorentz invariance of the photon phase-space density, leading to I′ ∝ (f′/f)⁴ for broadband radiation.

Get Dr. Elliot McGucken Theoretical Physics’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.Subscribe

Here, we derive the McGucken Invariance, which unifies the time of arrival, frequency shift, and intensity transformation into a single invariant quantity.

Theoretical Framework

Consider points A and B on the embankment, separated by 2L, with lightning strikes occurring simultaneously at t = 0 when the train’s midpoint M′ coincides with the embankment’s midpoint M. The train moves at velocity v = βc to the right.

- Time of arrival:

- From B (approaching): τ_B = L / (1 + β)

- From A (receding): τ_A = L / (1 — β)

- Doppler shift:

- f′_B = f √((1 + β)/(1 — β))

- f′_A = f √((1 — β)/(1 + β))

- Brightness:

- I′_B = I ((1 + β)/(1 — β))²

- I′_A = I ((1 — β)/(1 + β))²

Substituting these yields the invariant form.

Calculations (L = 1, c = 1)

- β = 0.2 γ ≈ 1.0206 Both signals yield 1.0206 * f² / I^(1/4).

- β = 0.5 γ ≈ 1.1547 Both signals yield 1.1547 * f² / I^(1/4).

- β = 0.9 γ ≈ 2.2942 Both signals yield 2.2942 * f² / I^(1/4).

Discussion

The McGucken Invariance encapsulates relativistic distortions in a frame-invariant manner for symmetric events, scaling with γ across velocities. This reflects the increasing asymmetry in perception at higher β. Potential applications include analyzing Doppler-boosted emissions in relativistic jets or high-energy particle experiments. While novel, it aligns with foundational relativistic radiative transfer.

Conclusion

We have introduced and verified the McGucken Invariance, extending Einstein’s framework to unify timing, spectral, and intensity effects. Future investigations may explore its generalization to curved spacetimes or quantum contexts.

Leave a comment